“Neo-Victorian texts not only rewrite the past and bring to the surface the so-far unheard (women’s) voices but also profoundly comment upon the present.”

– Dr. Aleksandra Tryniecka

Content Warning: This article includes discussions on historical gender roles, societal oppression, and post-colonial criticism, which may be sensitive for some readers. If you or someone you know is affected by issues related to gender inequality or societal expectations, consider seeking professional guidance.

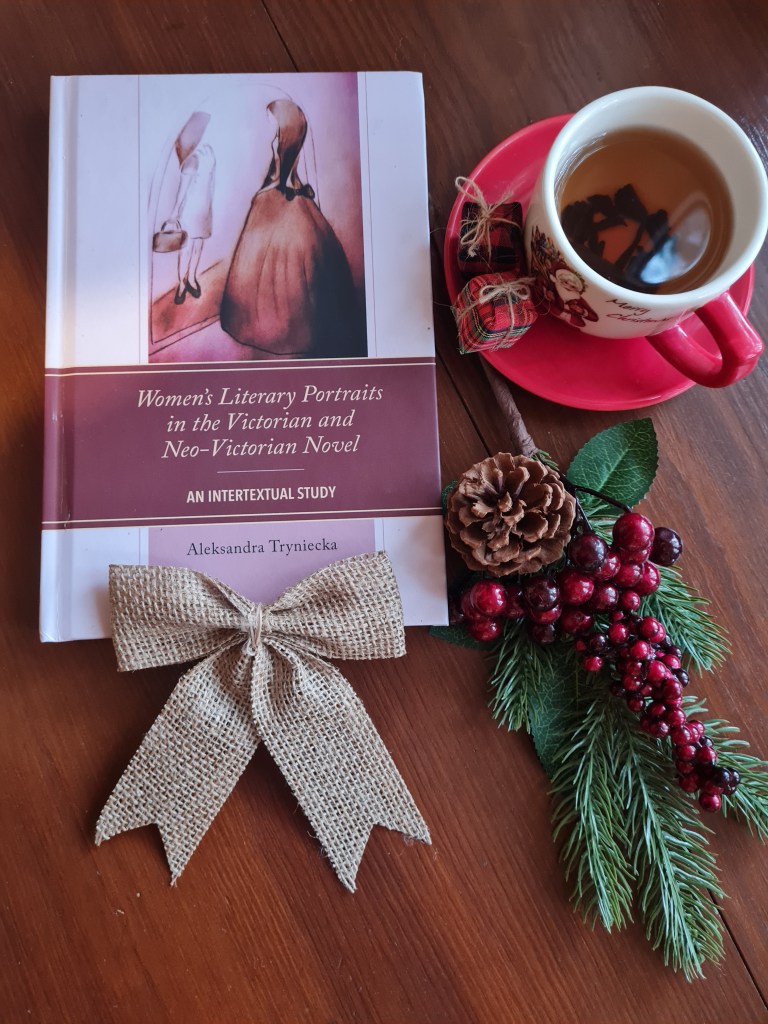

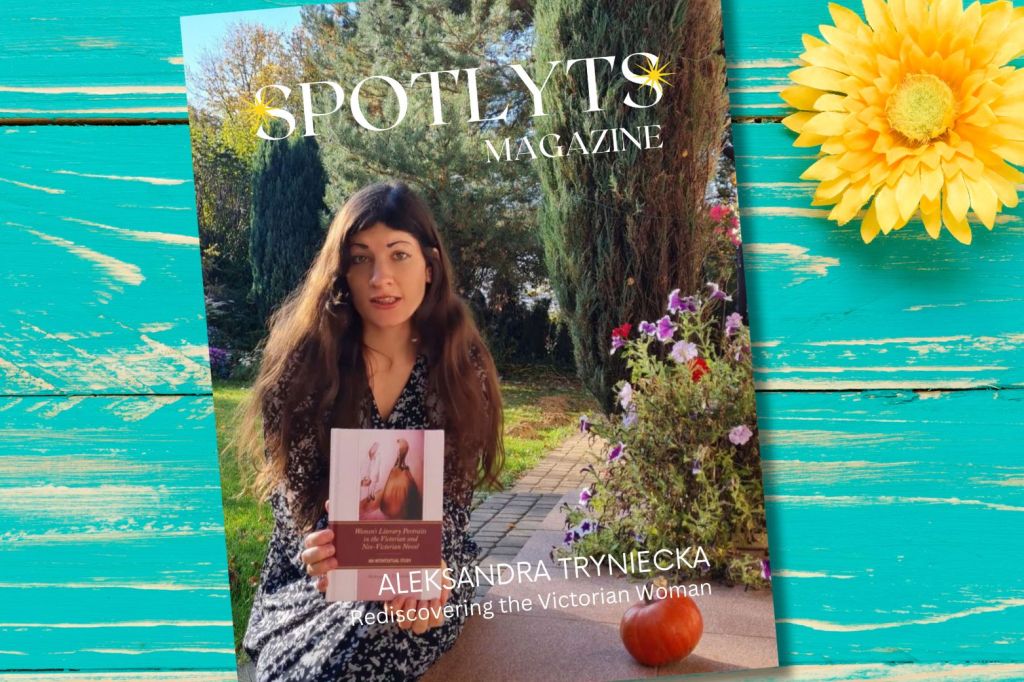

What can Victorian literature teach us about modern life? Dr. Aleksandra Tryniecka, an Assistant Professor, children’s author, and illustrator, goes deep into the world of Victorian and neo-Victorian literature to explore how women’s voices, identities, and struggles remain relevant today. In her acclaimed book, Women’s Literary Portraits in the Victorian and Neo-Victorian Novel, Aleksandra bridges the gap between the 19th century and the present, offering fresh perspectives on literature’s enduring role in shaping culture. Join us as we have this interview with Aleksandra about her inspirations, favourite literary heroines, and how she brings the past to life in a modern world.

What first sparked your fascination with Victorian literature and its modern reinterpretations?

I became deeply fascinated by Victorian literature as a teenager upon reading Wilkie Collins’ acclaimed detective novel The Woman in White (1859/1860). During this time, I was still working on my English, but I fell in love with the novel so deeply that I read it in its entirety while using a dictionary. From that moment on, I began reading countless Victorian and Neo-Victorian novels.

When it comes to the Neo-Victorian genre, these texts rewrite their Victorian predecessors in a modern vein while rediscovering and bringing to the surface the Victorian past. While they endow numerous unheard literary characters with new, modern voices and reconstruct the past, approximating it to the modern perspective, they also comment on the present while bringing it closer to the bygone. The relationship between the past and the present in Neo-Victorian texts is based on the notion of mutual interest.

My fascination with Neo-Victorian fiction began during the first year of my doctoral studies at Maria Curie-Skłodowska University. I was researching modern narratives drawing on the Victorian past and encountered Gail Carriger’s Soulless (2009), featuring the strong, assertive character of Alexia. From that day, I have been studying both Victorian and Neo-Victorian novels, especially concentrating on women as literary characters, their fashion, roles, behavior, and placement in society at large.

Your book examines how Neo-Victorian novels revisit women’s roles in the 19th century. Why do you think these stories still resonate today?

I believe that the stories concentrating on women’s roles in the 19th century still resonate today as, on the one hand, everything has changed, but, on the other hand, nothing is truly different. Charles Dickens famously stated, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.” I believe that we can safely assume the same about our times.

We often examine the 19th-century past as if it were some kind of entity detached from or contrasting with our present. However, in truth, Victorians were quite similar to us—from their moral ambiguity to their historical placement. For instance, while we are overwhelmed by technological progress, Victorians faced similar anxieties in the era of industrial changes and the social unrest these changes triggered. Women were meant to belong to domestic spaces, and yet, in the 19th century, I could offer several examples of assertive women who thrived independently, opposing the convention.

Going back to the present, we find women in ambivalent positions as well: on the one hand, they are supposed to be independent and professionally successful while, on the other hand, they are still looked down upon when not fulfilling their conventional domestic roles. Examining the concept of society at large, women are usually placed between numerous contrasting expectations and, at the same time, with inventive possibilities at hand.

I discovered that studying women as literary characters against the background of society enables one to comprehend the nature of society as such. Women are always balancing between the private and public, expected and unforeseen, revealing the nature of society and its foundations regardless of time and age.

It is also essential to highlight that Neo-Victorian texts not only rewrite the past and bring to the surface the so-far unheard (women’s) voices but also profoundly comment upon the present.

If you could invite any Victorian or neo-Victorian literary heroine to dinner, who would it be, and what would you ask her?

I smiled and instantly thought about Alexia in Gail Carriger’s “Soulless”. This heroine allowed me to discover my interest in Neo-Victorian fiction! I also admire Alexia’s assertiveness and her inner strength. She is a fabulous character with deep self-awareness and self-confidence. I know that we would be able to discuss everything – from our shared learning passion to our favourite tea! I would definitely ask her to help me select the best Neo-Victorian dress – Alexia is always beautifully dressed in Carriger’s novels, and she perfectly combines elegance with practicality – that is the key to steampunk and Neo-Victorian fashion. Also, I would be curious to learn about her thoughts concerning our modern world. If she would emerge from the pages of the novel, I would definitely ask her to comment on the state of affairs in our present.

When it comes to Victorian literary characters, I am thinking about the eponymous Woman in White in Wilkie Collins’ novel. Poor, misunderstood Anne Catherick would definitely feel better in our world – regardless of its chaotic and violent nature – for, at last, she would be allowed to preserve her individual style of dressing in white clothes (without explaining herself and being accused of insanity), as well as her personal integrity would remain intact. I perceive Anne Catherick as such a gentle and noble heroine – I believe that we would have quite a lot to share over our afternoon tea. Lastly, I was thinking about Catherine from Emily Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights” – while I applaud her strong personality and independent nature, I am not thrilled by her actions towards Heathcliff. I would like to send her a letter to explain it further.

How do you approach balancing academic rigor with making your work accessible to general readers?

Thank you so much! I think that this is one of the key points to consider when it comes to merging academic realities of conducting and presenting research with the world of literature and history Lovers. Quite often, these worlds are already merged in a harmonious way yet, sometimes, scholarly works tend to be slightly exclusive in their nature, presenting a given topic in a highly formal, academic way that, on the one hand, is deeply engaging but, on the other hand, might lack the spark of excitement or endeavours to engage in a more intimate dialogue with the readers. While writing “Women’s Literary Portraits in the Victorian and Neo-Victorian Novel”, I was trying to connect these two equally interesting worlds, so that I could possibly offer my readers – literature and history Lovers – an engaging research presented in a possibly friendly manner that would allow them to connect with the text on more personal and intimate levels. I hoped to write an academically intriguing book that my readers could read over a cup of coffee. I simply hoped to tell a story I am passionate about while not depriving my readers of the intricacies and scholarly details that academia offers. After all, I’d been conducting the research for my book for more than ten years! I began as soon as I embarked on my PhD journey, and when I completed my PhD thesis, I continued working on this project, hoping to bring it even closer to my Readers.

At the same time, new publications related to the topic of my research would be emerging each week, and I had to constantly rethink and reconstruct my work to make it as accurate as possible. Of course, there came a moment when I simply had to stop writing! “Women’s Literary Portraits…” contains an expanded theoretical introduction prepared especially for those readers who would be interested in more academic and formal aspects of analysing texts. I believe that it was important to me, as a scholar, to offer this introduction to every literature and history Lover. However, this introduction was shortened and rewritten for those readers who might find theoretical analyses quite intimidating. I invite them to readily dive into the second chapter – straight into the Victorian past!

What’s a modern paradox about women’s roles that you find most striking when compared to the Victorian era?

I began conducting my research in my early twenties, and I believe that it allowed me to analyse the concept of society at large. In fact, I was quite surprised with my findings! Suddenly, I discovered women in the nineteenth-century novels facing situations that appeared quite modern and, conversely, women in the modern texts judged from the nineteenth-century perspective. Noticing how similar are the assumptions concerning the nineteenth-century and modern women allowed me to slightly detach from certain socio-cultural expectations and understand that what is truly important is each woman’s individual journey, regardless of the age one lives in.

The modern paradox about women’s roles in the present-day society is that these roles have not really changed. Instead, there appears to be even more pressure focusing on women’s lives – women are no longer confined to the domestic sphere but, at the same time, they are expected to balance successful careers with a happy family life. There is an ongoing debate about women’s equal opportunities where “equal” appears to mean “doubled”, while “opportunities” stands for “expectations”. At the same time, beginning from the Victorian era, there are some emerging notions in society that, in order to gain her freedom, women should perhaps become more like men.

On the whole, the modern paradox about women’s roles in society is that these roles cannot be reasonably realised and require a superhero who would skilfully balance a perfect career with an ideal family life and still appear rested, energetic and attractive. Such harmful – because highly unrealistic models are unfortunately often proliferated by social media. I also don’t believe in the solution of becoming more like men in order to gain freedom while giving up on one’s uniqueness. Here I would like to return to Neo-Victorian fiction once again, where women such as Alexia are portrayed as strong, assertive, intelligent and independent, yet nurturing their feminine and elegant side while, at the same time, not being afraid to admit to insecurities and doubts.

Can you share how specific novels, like Jane Eyre or Wide Sargasso Sea, influenced your work and perspective?

I believe that Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) and Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) became the two classics strategically determining the perception of the same sort – thus allowing me to further reflect on the potential of the nineteenth-century and neo-Victorian novels presenting women as literary characters. Rhys’ modern prequel commenting on the original narrative written by Brontë offers a potential look behind the scenes – a narrative fulfilment for Brontë’s woman in the attic. Initially demonised in the original narrative, Bertha – or Antoinette – as named by Rhys, regains her personality, integrity and the lost voice. In this light, Rhys’ text reshapes one’s perception of Brontë’s Jane Eyre: it allows for the appreciation of the character of Bertha and triggers a negative perception of Mr. Rochester. However, I believe that both novels can still be read and analysed separately. One can merge them into a unified narrative, or one can read them separately as socio-cultural testimonies of a given era. While analysing literature, it is vital to remember that each text was anchored in a given socio-cultural reality. While creating the character of Bertha, Brontë most probably did not even realise that she might be demonising or undervaluing her. Instead, her aim was to present the unwavering moral courage of the main protagonist – Jane. The consciousness of our present-day era is different, and we are sensitive to the issues of post-colonialism and the notions of unheard and oppressed voices. Yet, I still read Jane Eyre as a beautiful and hopeful Bildungsroman: the tale of a young orphaned woman whose moral ideals allowed her to find personal happiness with the highly intricate and alluring Mr Rochester. At the same time, I deeply value and read Wide Sargasso Sea as a beautiful, redeeming narrative of a young woman in a liminal socio-cultural position in search of her own home whose heart was broken to the point of madness, and whose narrative allowed her to forever transform from the enigmatic Bertha locked in the attic into a gentle and beautiful Antoinette desperately searching for her own roots. Arguing that we are always meant to read both narratives as one text – the blend of Jane Eyre and Wide Sargasso Sea – would also not offer justice to these narratives, as they were shaped by different socio-cultural realities. This is such an interesting phenomenon about Victorian and Neo-Victorian fiction – it inherently mirrors our socio-cultural placement and perspective and it offers us profound lessons about ourselves.

In your research, did you discover a lesser-known Victorian or neo-Victorian work that you think deserves more recognition?

I would definitely invite the fans of Charlotte and Emily Brontë to reach for their youngest sister’s novel – Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of the Widefell Hall (1848). It is the second novel published by Anne during her short life and, as I believe, it deserves much more recognition on the literary scene. While Charlotte’s novels are well-known for imparting moral lessons and for portraying shy yet assertive heroines in fairytale-like places also frequented by gloomy, yet passionate and intriguing male figures, Emily’s Wuthering Heights (1847) verges on mysticism, madness, fantasy and passion. The Tenant of Widefell Hall merges both of these elements into a captivating and elegant narrative.

Also, I would like to recommend Anthony Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her? (1864) – a surprisingly modern novel written in the second part of the nineteenth century – a must-read for every young woman embarking on the journey into adulthood – never getting old!

As a children’s author and illustrator, how do you see the influence of Victorian storytelling techniques in your creative work?

I’ve heard from several readers that my novels dedicated to Bunky are slightly Victorian in nature when it comes to their setting and the interior of Bunky’s house or some instances of the language used in the narrative. I believe that an important nineteenth-century storytelling technique is allowing the readers to gently step into the story, letting the narrative unfold gradually so that the novel becomes the readers’ literary home. I love how Victorian novels build the notion of literary worlds in which the readers can remain for a longer time. This is the reason why both of my novels: “Bunky and the Walms: The Christmas Story” and “Bunky and the Summer Wish” are two hundred or three hundred pages long. I hope that they can become the readers’ home and their safe, happy place. I also would like to offer my readers the world and characters who are fully-fledged and presented in the smallest details so that they could become their friends. I am also fascinated by the beautiful language in the nineteenth-century novels.

What advice would you give to someone starting their own journey into Victorian or neo-Victorian literature?

Every text – no matter what kind of text it is – offers a glimpse into a given socio-cultural reality. In this sense, every text is knowledge. However, my advice would be to remember that while selecting a given Victorian work to read, we are selecting a specific nineteenth-century reality and, even though neo-Victorian works strive to rewrite it, we also need to accept the past for its uniqueness with all its benefits and drawbacks. Also, I believe that neo-Victorian novels should not reject or remove the past – for no matter what it brought and offered, it is a part of our journey – otherwise, we wouldn’t be here and now. There are currently voices in the academia that the bygone should be utterly criticized or obliterated. I believe that if it was done, we would obliterate ourselves, as our history is linear.

If a young reader asked you why Victorian women’s stories matter today, what would you tell them?

I believe that my answer would be that history is still, to a large extent, running in circles, while Victorian women are inherently a part of a wider socio-cultural perspective – with their joys, hopes, anxieties and dilemmas. They are a part of our society and a part of the modern discourse and expectations – as always, skilfully balancing between the private and public, even though our times are supposedly changing. Somehow we are still eagerly reaching for Victorian novels, revisiting them in neo-Victorian narratives. Somehow everything we know about the past will be reflected in our present – it’s inscribed into our “here and now” so that, hopefully, we can make better or improved choices in the future.

“Women are always balancing between the private and public, expected and unforeseen, revealing the nature of society and its foundations regardless of time and age.”

– Dr. Aleksandra Tryniecka

Links

Share Your Insights

Share your thoughts! What do you think about the themes explored in this interview?

- What modern parallels do you find most striking when comparing past and present societal expectations?

- Which Victorian or Neo-Victorian work has had the greatest impact on you?

- How do you see women’s roles evolving in literature today?

DISCLAIMER: Spotlyts Magazine does not provide any form of professional advice. All content is for informational purposes only, and the views expressed are those of individual contributors and may not reflect the official position of Spotlyts Magazine. While we strive for accuracy and follow editorial standards, we make no guarantees regarding the completeness or reliability of the content. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and seek professional assistance tailored to their specific needs. Any links included are for reference only, and Spotlyts Magazine is not responsible for the content or availability of external sites. For more details, please visit our full Disclaimer, Privacy Policy, and Terms of Service.

Highlight of the Day

“With great power comes great responsibility.”

— Uncle Ben, Spider-Man

Leave a comment