“I simply love language—the magic that transforms thoughts into words and shapes.”

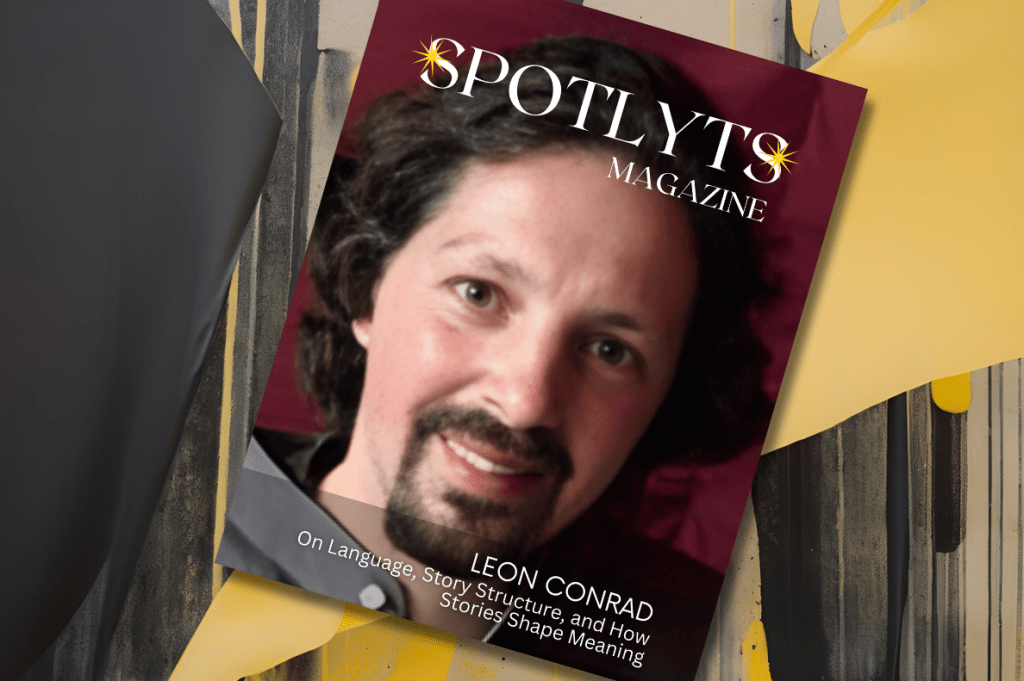

– Leon Conrad

For Leon Conrad, language has always been a system of meaning, pattern, and comprehension rather than just a tool. Conrad explores the workings of stories and their enduring power in Story and Structure. In this interview, he talks about language, research, education, and the influence of stories on our thoughts, writing, and daily lives.

Leon, thank you for joining us. Could you start by telling us a little about yourself, your background, and what led you to become a writer?

What led me to become a writer? I wish I knew. I simply love language—the magic that transforms thoughts into words and shapes; the patterns we form in our minds into meaningful, musical sentences, clauses, phrases, words, syllables made of vowel sounds and consonant sounds—the magical building blocks of language.

Part of the fascination, perhaps, was that I was surrounded by many languages while I was a child. My mother was from a large Coptic Egyptian family and spoke French, English, and Italian fluently; she also knew Arabic and a smattering of other languages that she dropped into conversations creatively. My father was from Poland, and I remember learning a bit of Polish when I was very young, although I’ve forgotten most of it now. I continue to be fascinated by the similarities and differences in word choices and approaches to communication across different languages. Why, for instance, does “fire” sound softer in French (“feu”) than it does in Spanish (“fuego”)? Is it because the sun is hotter there? But then, the Arabic word is different again (“nar”).

My approach to writing comes from two unforgettable encounters I had with an experienced and spellbinding oral storyteller as a schoolboy—and also from a love of books and having them read to me as a child. The oral delivery of a story is always the driver for me; it continues to inspire me both as a writer and as a storyteller.

How did the idea for your book come about, and what inspired you to bring it to life?

My book, Story and Structure, is the third solo-authored book I’ve had published. It’s the one I’m most pleased with so far. It’s also the one that’s won the most awards. It came about totally unexpectedly when I read something about “the story of Cinderella” that stopped me in my tracks. It was in The Cambridge Guide to Narrative by H. Porter Abbott, an author I greatly admire. He’s written cogently and convincingly about narrative in general and about the works of Samuel Beckett. But in this book, the thought that stopped me short was this: “What is necessary for the story of Cinderella to be the story of Cinderella? … This is a question that can never be answered with precision.”

How come? I thought. Does he have a crystal ball? Yes, there are well over 1,000 versions of the story that have been identified. They differ significantly, but many also feature key elements that are similar, if not the same. And yet, not all of them do—so what is it that makes “the story of Cinderella” identifiable as such?

Story and Structure reveals the answer. It was the result of a 10-year research project which reveals new information about how story “stories” (I use the term “stories” here as a verb), even though we’ve been telling stories for literally thousands of years. It explains not just how stories work, but why different story structures exist. And it reveals what makes the Cinderella story recognisable as a Rags to Riches structure story, why not all Cinderella stories conform to that structure, and what the other structures are that Cinderella stories could follow.

Anyone who’s interested in stories—whether as someone who appreciates them for what they are or as someone who wants to learn how to tell better stories—from writers and screenwriters to marketing and advertising professionals, and students trying to communicate a story through an essay or dissertation, will benefit enormously from getting to grips with the structures and underlying purpose that each one has, as outlined in the book.

Can you walk us through your process for writing and developing the story? How do you shape ideas into a complete narrative?

In Story and Structure, I distinguish between the way story (as a phenomenon) flows on the one hand and the way stories can be told on the other hand. Any story needs a character, right? I mean, can you think of a story that would work which doesn’t have at least one character in it? Think about it … even a piece of descriptive writing is told from a narrator’s point of view! And as stories flow at the level of story structure, the events which happen in each individual character’s story line in chronological order are revealed. Story structure works by following the events that happen in an individual character’s story line as they happen “at the time of the tale.”

If Story and Structure focuses on what happens in a story “at the time of the tale,” what about what happens in a story as it unfolds “at the time of the telling”? After all, when it comes to telling the story, you can shift things about—flashbacks, foreshadowing, implications, backstories … all these are techniques which involve rearranging events so they’re revealed in an interesting way “at the time of the telling.”

Telling a story in a compelling way depends on a writer’s (or storyteller’s) skills, on the art of crafting stories. This is something I develop more in my follow-on book, Master the Art and Craft of Writing: 150+ Writing Games to Liberate Creativity. After all, writing should—and can—be playful and FUN!

What themes or messages were most important for you to convey in your book?

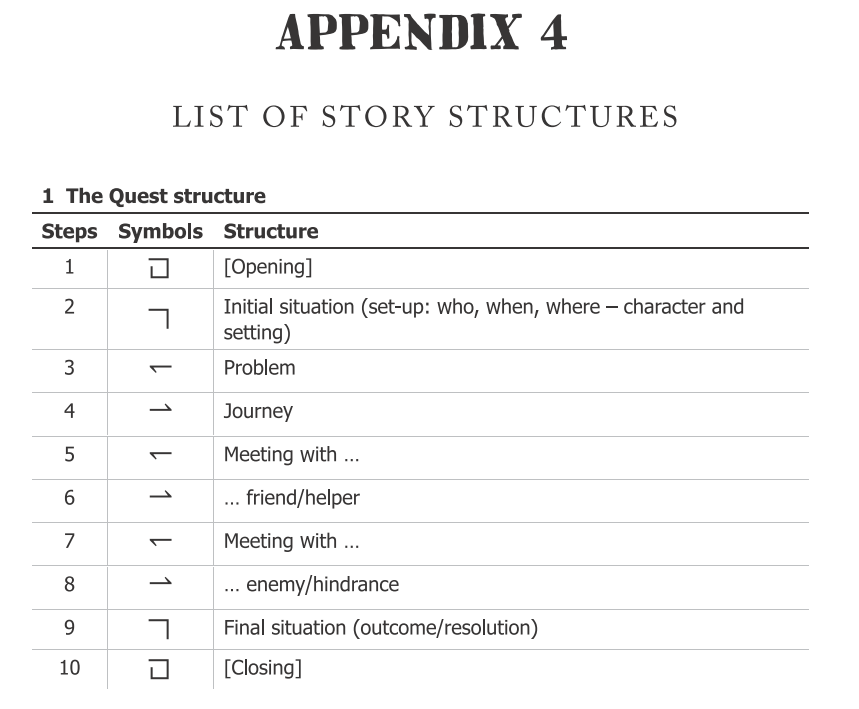

One of the key takeaways from Story and Structure is the skill of following the ebb and flow of tension and release in any story. I use six simple symbols drawn from a key work (Laws of Form) by my mentor, George Spencer-Brown. It was published in 1969 and has since become a cult classic. I was his last student, and he guided me through the work himself.

The approach is simple and, in many ways, visually intuitive. Take two of the symbols: the backwards and forwards barbs (↽ and ⇀). These symbolize a build-up of tension and a release of tension respectively. While the approach is simple, it’s the first time that Spencer-Brown’s work has been applied comprehensively to the study of story structure in this way.

Another key takeaway is the importance of breaking a story down into what happens in individual characters’ story lines. In the version of the story of Cinderella that most people know, even the mice and the pumpkin have their own story lines. It’s up to the storyteller which story lines they choose to focus on in their telling of the story—in their version of the narrative. Thinking about each character in terms of what happens in their story line brings a depth and insight into the storytelling process that wouldn’t necessarily have been there otherwise.

The other thing that I should mention is the importance of reducing the events in a character’s story lines to their bare bones. That means only focusing on the essential elements without which the story couldn’t be told. The approach is flexible. You can expand a story indefinitely; the approach will still work. But in order to determine the fundamental story structure or structures at play in a character’s story line, the events need to be condensed down to the barest essentials.

Receiving the Spotlyts Story Award is a notable recognition. What does this award mean to you, and how do you feel it reflects your work?

It’s both flattering and humbling to have received this award, which highlights the importance of stories and storytelling in building communities, encouraging good conversations and debate, and awakening the power of the imagination—human qualities that are more important than ever in an age increasingly dominated by “Artificial Insanity,” as I sometimes call it.

I’m extremely grateful for my work to be recognised for its contribution to the art of storytelling, particularly since the Spotlyts Story Award promotes the art and power of storytelling and brilliantly complements the research I’ve been conducting in the 10 years that led up to the publication of Story and Structure. I’m honoured to have our two endeavours be joined through this prize.

I’m delighted that the book has continued to gain recognition and interest since its publication. It has much in it that readers will find useful and interesting in terms of why we have different story structures (I list 18 that I identified over my 10 years of research, and I’ve not found any new ones since). What’s fascinating is that these structures arise in and from consciousness. They work “with the grain of the brain,” as a storyteller colleague of mine, Giles Abbott, is fond of saying.

I’ve benefited along the way from the work and insights of many writers, storytellers, and colleagues, and the award is as much a recognition of their work and contribution as it is of mine.

Have there been specific milestones, experiences, or moments in your writing journey that stand out as particularly formative?

I love trying to find satisfactory answers to questions that we don’t yet seem to have satisfactory answers to—questions like “What makes the story of Cinderella the story of Cinderella?” to give one example. Sometimes, to get to a satisfactory answer, all you need is a different way of looking.

When my search for a satisfactory answer to this question stalled, I put the project to one side while I tackled a different question: Why, in the Liberal Arts tradition, did some writers list the three Trivium subjects as Grammar, Logic, and Rhetoric, and others as Grammar, Dialectic, and Rhetoric? In the process, I looked at ways of symbolising logical relationships, and that led me to the work of George Spencer-Brown and his book, Laws of Form. I was intrigued by what I’d found—particularly by the story-based introduction to it on a website curated by a fan of his, George Burnett-Stuart: The Markable Mark (markability.net).

When I found Spencer-Brown’s telephone number on a web page which invited interested students to phone him “between the hours of 4 am and 8 am UK time,” I was even more intrigued. I plucked up the courage to phone him—at the tail end of the time frame given. His manner of speaking was old-fashioned: clear, well-articulated words and sharp, insightful thoughts, with a wry sense of humour. He agreed to tutor me. When the series of tutorials on his work ended, a friendship developed, and we continued to engage on a weekly basis until the end of his life.

In Story and Structure, Spencer-Brown’s methodology has helped me tell the previously untold story of how story works. It provided me with the key that unlocked the satisfactory answer I was looking for. George Spencer-Brown died in 2016. The book is dedicated to his memory.

How do you approach connecting with readers through your storytelling? Are there ways you hope your work impacts them?

When I’m not writing, I tutor and teach creative writing, and I use many techniques from the storytelling world in my teaching—techniques which aren’t limited to telling stories. Some of the most impactful events in my teaching career so far have resulted from teaching students about story structures.

A few years ago, Giles Abbott and I were conducting a series of workshops in a school in South London around using story structure to empower creative writing. We taught the young writers the Quest structure. It’s a structure you find in the story lines of The Three Little Pigs. You may be familiar with the well-known story in which they encounter a big bad wolf who huffs and puffs and blows two of their houses down, but ends up defeated at the end.

The structure goes like this:

- A story opens.

- We meet a character—who, when, where, in what condition.

- They have a problem (a backwards move: ↽).

- As a result, they go on a journey to seek a solution (a forwards move: ⇀).

- On the journey, they meet a friend or helper. The meeting stops them in their tracks (↽).

- Once they have received the help, they can progress further (⇀).

- They meet an enemy or hindrance. Once again, they’re stopped in their tracks (↽).

- They overcome the enemy or hindrance (⇀).

- They solve the problem.

- This allows the story to close.

The structure, when reduced to its bare bones, is formed of three backwards–forwards pairs framed by the essential elements listed above. In essence, it goes like this:

(Opening and character in initial situation)

↽ ⇀ ↽ ⇀ ↽ ⇀

(Character in final situation and closing)

The students used the Quest structure to produce compelling stories, developing them, extending them, and elaborating on them over a few sessions. One particular girl, however, surprised us.

She came to us and asked to tell us a story about a problem she’d encountered at home. She’d been wrongly accused by her parents of having done something. In fact, she hadn’t done it; her younger brother had, and she felt that he should’ve been punished for doing it, not her. Her parents had sent her to her room. When her tears had subsided, she decided to use some internal friends and helpers—her powers of communication and her ability to take action—to see justice restored. She got up, dried her eyes, went downstairs, and calmly talked to them about the injustice of the situation that they’d put her in. When they confronted the younger sibling, he admitted to having done the deed and accepted the punishment they gave him.

As she came to the end of the story, she thanked us.

It wasn’t us that she ought to thank, I said. It was the power of story itself.

She’d used the Quest structure to solve her problem. She’d instinctively understood that the power of story goes way beyond the stories we tell. Understanding how story structures work can help us live our lives more flowingly.

Story structures differ because they’re emergent responses to different types of problems. Each story structure is a natural expression that consciousness produces as it seeks the ideal solutions to a given type of problem that it experiences. This is one of the original and ground-breaking insights revealed in my book.

What challenges have you faced in developing your voice or style as a writer, and how have you navigated them?

Developing one’s own voice as a writer is sometimes challenging because it’s so easy to be influenced by what’s out there—to want to do what everyone else does. But despite the challenges, the ongoing process of developing an individual style can be a lot of fun. Every book I’ve written and published—from books of children’s poems to history riddles to educational books, right up to books on creative writing—has taught me something.

The operatic singer Jessye Norman was asked late in her career whether she ever listened back to her own recordings. “No,” she said (and I paraphrase). “I make a rule not to. Once the recording is done, it’s done. It’s a snapshot of the best performance I could give at that time. That’s all.” She was adamant that, for her, it was more important to live in the moment and look ahead than to go back over a past performance and judge or evaluate it. There were other ways of improving, learning, and progressing. I feel the same about writing.

Every book I’ve brought out has been a springboard to an improvement in my approach to writing. I can’t think of a time when I’ll stop learning—there’s so much to cover. Of course, it’s hard work, but it’s also a fun and rewarding process. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Are there other projects, stories, or creative pursuits you are currently exploring, or that you hope to explore in the future?

Yes, I’m always working on something. I continue to be intrigued by the connections between the classical Liberal Arts, for one thing. I’m also intrigued by the question of why an inch is as long as it is. Getting to a satisfactory answer to that question has taken me deep into the world of ancient metrology, which is a fascinating area of research that few people have ventured into.

Beyond that, I’m working on companion works to my book History Riddles. My next planned work is Bible Riddles—a book of riddles based on stories from the Bible and some of the cultural events that those stories have inspired. I’m also working on a collaborative East-meets-West embroidery project with some of the master craftsmen in the Khayyameyya community—the traditional so-called tentmakers of Cairo—which stems from my interests in historic needlework and in engaging with living traditions of craftwork and the tradition-bearers who honour those long-standing practices in increasingly challenging circumstances.

How do you balance inspiration from real life, imagination, and research in your storytelling?

There’s no gap for me between story and real life. Story structures pervade the very fabric of existence. I value the common ground, and I’m inspired by it. To know that the same structure that is part of the story of The Three Little Pigs is also the structure that allows a top-class academic essay to flow well is liberating.

If only educators linked these structurally similar patterns up in schools when teaching young learners creative writing, their work would be so much easier, and students would arguably find the process more fun and more joined-up. The students wouldn’t just be better writers as a result; they’d learn how to flow better as human beings by using and drawing on story structures at a deep level in their lives.

If you were to write your bio in your own words, what would you say? Looking ahead, what kind of long-term impact would you like your work to have?

I’m a traditionally published author and storyteller. I’ve been a regular columnist, had articles published in journals and magazines, written theatre shows, and contributed to radio programmes. I teach creative writing and am a meticulous and collaborative editor and story structure consultant to both fiction and non-fiction writers.

My multi-award-winning book Story and Structure (The Squeeze Press, 2022) reveals new information about story and how we can live more harmoniously by following the “laws of story.” It’s based on the methodology in George Spencer-Brown’s remarkable book, Laws of Form. I was his last student, and he guided me through the work himself. My book outlines how story works “at the time of the tale,” where events unfold in chronological order. But this is not necessarily how stories are told.

In my most recent book, Master the Art and Craft of Writing (Aladdin’s Cave Publishing, 2024), I introduce over 150 fun games to liberate creativity. The book focuses on how to make stories interesting to readers or listeners based on how events are related “at the time of the telling.”

My TEDx talk, The Magic of Words, with marimba player Aristel Škrbič, is on YouTube, and my free online course taking readers through Laws of Form, available also on YouTube, has had over 33,000 views (as at January 2026).

As a storyteller, I’ve been studying the Drut’syla Midrash, a little-known oral tradition and approach to latticing stories, with storyteller Shonaleigh Cumbers since 2015.

I’m co-founder and lead trainer at The Academy of Oratory (previously The Conrad Voice Consultancy), and I tutor students across the world using an integrated approach to a classical Liberal Arts education through The Traditional Tutor, as well as being Orator in Residence at The Next Society Institute.

“Understanding how story structures work can help us live our lives more flowingly.”

– Leon Conrad

Related

Spotlyts Story Awardee: “Story and Structure” by Leon Conrad

Is storytelling closer to science than magic? Discover how Leon Conrad reveals the hidden mathematics behind narratives and how this understanding can transform the way you experience stories forever.

Keep readingShare Your Insights

What are your thoughts on the power of story?

- How has story influenced the way you learn or communicate?

- Have you ever noticed patterns in the stories you love most?

- Do you think storytelling skills apply beyond writing and books?

DISCLAIMER: Spotlyts Magazine does not provide any form of professional advice. All content is for informational purposes only, and the views expressed are those of individual contributors and may not reflect the official position of Spotlyts Magazine. While we strive for accuracy and follow editorial standards, we make no guarantees regarding the completeness or reliability of the content. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and seek professional assistance tailored to their specific needs. Any links included are for reference only, and Spotlyts Magazine is not responsible for the content or availability of external sites. For more details, please visit our full Disclaimer, Privacy Policy, and Terms of Service.

Highlight of the Day

“With great power comes great responsibility.”

— Uncle Ben, Spider-Man

Leave a comment